On Women in Church Leadership

A position paper from the session of Christ Church Bellingham on ordained & commissioned officeholders, representative participation in worship & women exercising teaching authority.

This position paper gives practical expression to the biblical view developed in the background paper, “Offices and Officeholders.” The CCB Session wishes to address in particular three areas of our church’s life that will benefit from greater clarity in our teaching and more consistent outworking in the shared life of our congregation:

• Understanding the similarities and differences between ordained and non- ordained church officeholders;

• Establishing a framework for determining who participates in a representative fashion in public worship, and in what ways;

• Explaining our interpretation of the meaning of Paul’s prohibition in 1 Timothy 2:12 with respect to women teaching or exercising authority over men.

ORDAINED & COMMISSIONED OFFICEHOLDERS

In “Offices and Officeholders,” an office is described as any specific vocation or formal role, to which someone is authorized by God, either as mandated by Scripture or established in the wise judgment of the church. The New Testament mandates only two offices, elder and deacon; but the church has often formally instituted additional unordained offices—whether traditional lectors and acolytes, or contemporary college ministry directors and women’s ministry coordinators. In practice, however, many evangelical Christians today (including many in our tradition) assume that holding office in any formal way is restricted to the two ordained vocations of teaching or ruling elder and deacon—the other positions may be valuable, but they’re certainly less “official.”

There are faithful motives behind this assumption; it’s good to affirm the Bible’s clear teaching about the uniqueness of the two New Testament offices of elders and deacons, ordained by God through previously ordained officeholders and confirmed by the congregation who elects them on the basis of the explicit qualifications in 1 Timothy 3 and Titus 1. This is especially important in a culture that tends to ground a person’s sense of calling in, “What am I passionate about and good at?” rather than, “What does the Bible say and what does the church confirm?” And in recent decades, many churches have decided to retain the Bible’s teaching about the importance of the ordained offices while ignoring the Bible’s teaching about ordination being restricted to qualified men.

But this risk shouldn’t lead us to lose sight of the Bible’s consistent view that the dignity and responsibilities of holding offices and being officeholders belong in some way or another to all human beings. And especially in the one body of Christ with its many complementary members, we should affirm a broader and richer scope for officeholding—that is, for believers to occupy God-authorized, official vocations in the church—than a more typical narrow application only to ordained officers. The biblical definition of an office given above applies across a number of formal roles held at CCB—by elders, deacons, diaconal assistants, and so on.

The CCB Session resolves to:

• Reflect in our preaching and teaching the Bible’s nuanced approach to offices and officeholders, acknowledging the uniqueness of the two ordained New Testament offices of elder and deacon while embracing God’s gift of a variety of authorized, official roles and positions within our congregation. This instruction must include the important distinction between someone being well-equipped for an office and being authorized to hold that office, since conflating these can easily lead to confusion or conflict.

• Follow the practice of many PCA congregations in referring to non-ordained officeholders collectively as Commissioned Church Workers. We believe this is wise in a contemporary American culture that widely assumes (for example) that if someone is called a “deaconess,” then her office must be identical to that of an ordained deacon.

• Restrict the titles of pastor/minister, elder, and deacon to those specific ordained officeholders. Many churches, in a well-meaning effort to affirm the importance of various roles, add these titles to (often unordained) positions like college pastor or children’s minister in order to make them sound more churchly and dignified. Unfortunately, this tends both to obscure the unique calling of ordained officeholders and to feed into an assumption that officeholders occupying other roles aren’t as legitimate or important.

• Create and maintain a list of the offices formally instituted by the CCB Session in addition to the biblically mandated offices of elder and deacon, along with a description of the rationale and expectations for each officeholder.

REPRESENTATIVE PARTICIPATION IN WORSHIP

Sunday morning is the pinnacle of our congregation’s life together, where we’re gathered to worship before the Father by Christ himself through their Spirit—not only in one another’s visible presence, but also in the invisible presence of the Trinity, the glorified saints, and all the angelic hosts of heaven (Hebrews 12:22–24). The dynamic character of this assembly is often described in the Reformed and Presbyterian tradition as a covenant renewal ceremony, where God meets with us to reconfirm his steadfast love and his promises to us, to call us to stand firm in our walk, and to strengthen us in our faith and love. In turn, we praise God for who he is and what he’s done, confess our sins, receive his forgiveness, are challenged and encouraged by his word, and receive grace and strength through the Lord’s Supper.

This means that every aspect of our public worship—every element of our liturgy— belongs in some way or another to this dynamic exchange between God addressing us and us responding to God. For every part of our service, we can ask, “Who’s turn is it to speak or act, God’s or ours?” Sometimes this speaking or acting is direct—for example, our songs and hymns are all sung collectively and we all profess the Apostles’ Creed together. Other times, this speaking or acting is representative—on God’s behalf or on the congregation’s behalf. For example, when someone preaches from the Bible, they’re speaking to the congregation on behalf of God; when someone leads congregational prayer, they’re speaking to God on behalf of the congregation.

Some churches restrict representative leadership in all areas of corporate worship to ordained officeholders, some make few if any formal restrictions, and others land somewhere in between. CCB’s practices haven’t been entirely clear or consistent in this regard. How do we decide who should or shouldn’t pray up front, collect the offering, or serve the Lord’s Supper? Our church stands in need of an explicit framework for determining who’s authorized to participate in congregational worship in such a way that their personal speaking and acting is representative of the speaking and acting of others—whether on God’s behalf or on behalf of the congregation.

The CCB Session resolves to:

• Be more biblically consistent in determining which areas of representative participation in corporate worship are open to whom, by following this general guideline: When someone is speaking or acting on behalf of God, that person must be an ordained officeholder in the PCA or one of our sister denominations, or someone in training for the ministry under the Session’s authority; when someone is speaking or acting on behalf of the congregation, that person may be any capable member in good standing (in the PCA or our sister denominations) authorized by CCB’s Session.

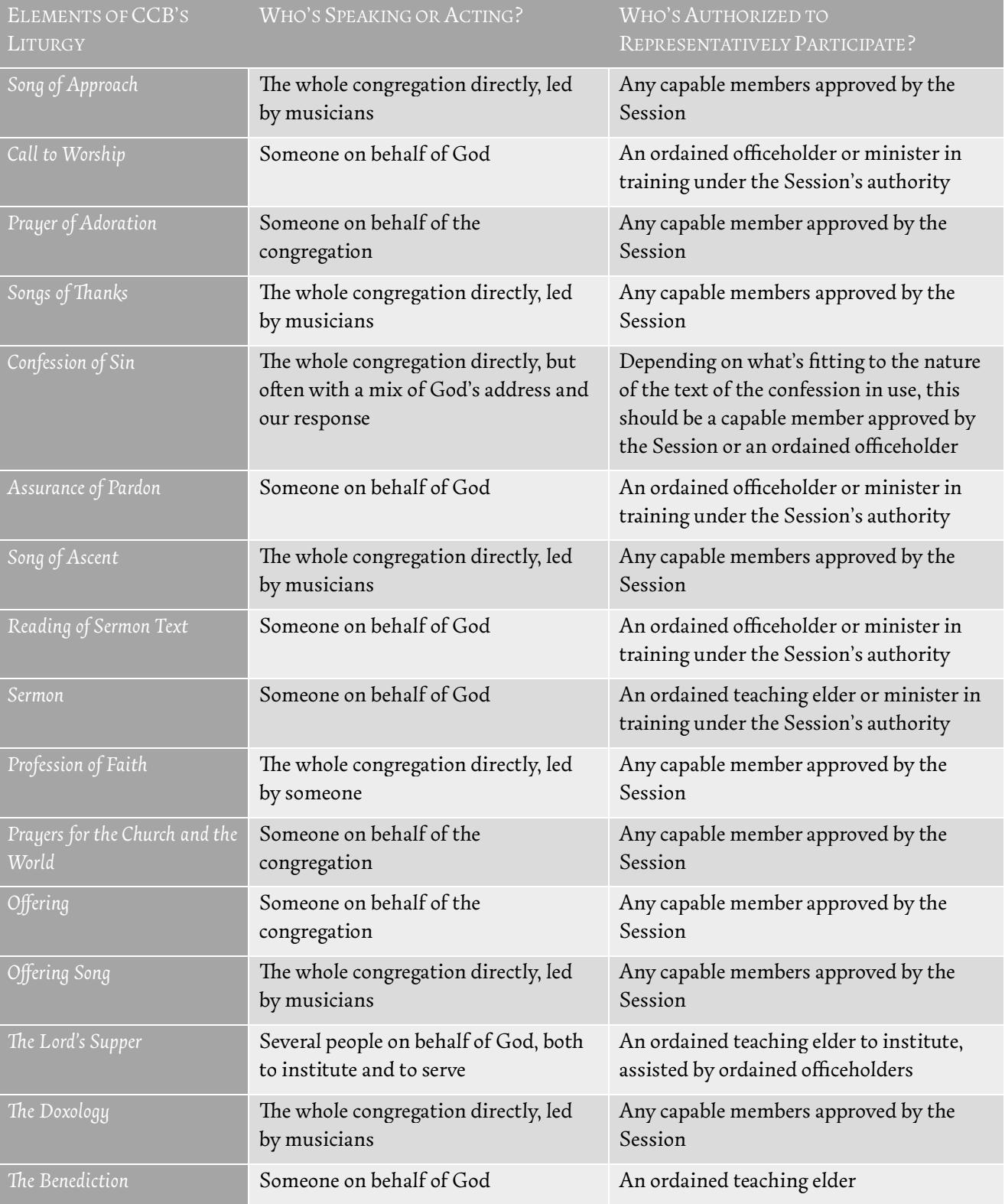

• Make certain changes in the way we think about and plan for our Sunday services in order to follow this guideline. Since we want to align our congregation’s liturgical involvement more consistently with the dialogical nature of corporate worship, we embrace the fact that doing so will open many areas of our liturgy to broader participation and more varied expression than we currently practice—and will restrict some areas more than we currently do. The table at the end of this position paper sets out in detail each of the back and forth movements of CCB’s liturgy and whether that element of the service belongs to God’s speaking and acting or ours. This gives us direction on who should be authorized to participate in a way that publicly represents others in those various movements. (The table attempts to represent a thorough outworking of the above guideline for dialogical covenant worship; in practical terms, however, such variety and breadth of representation won’t always be possible.)

WOMEN EXERCISING TEACHING AUTHORITY

In 1 Timothy 2:12, Paul expressly forbids women from “teaching or exercising authority over” men; instead, they must “learn quietly with all submissiveness” (verse 11). Many Christians over the years have taken this to mean that all roles—all offices—in the church that involve authoritative teaching (in particular authoritative teaching of men) are necessarily restricted to other men.

This is a more complex issue than it may appear; while these verses in 1 Timothy are clear enough, there are other passages that should provide additional context for our understanding of what Paul is (and isn’t) saying. Paul clearly isn’t saying that women are universally or inherently incapable of or unsuitable for teaching men because they’re women. After all, Paul in his second letter to Timothy commends him for being strong in the faith that was first in his grandmother Lois and his mother Eunice, from whom he learned the ways of being a faithful disciple of Jesus. Paul’s intent is to honor these women, not rebuke them (or shame Timothy for being taught by them). And examples of this sort of discipleship aren’t restricted to families. In Acts 18, we have the story of Apollos, a well-educated and eloquent Jew from Alexandria, showing up in Ephesus. Apollos understood the Scriptures and taught accurately about Jesus, but “only knew the baptism of John” (verses 24–25). When Priscilla and Aquila, a married couple who were celebrated ministry companions of Paul, heard Apollos preaching and teaching in the synagogue, “they took him aside and explained to him the way of God more accurately” (verse 26). Notice that they both instructed Apollos, which means not only that they were both extremely well trained, but that they both exercised the skill and gift of teaching in carefully and fully explaining the Christian faith to their new colleague.

Since the Bible commends examples of women teaching not only children in the home but even powerful men in the Christian community, what are we to make of Paul’s restriction against women teaching men in 1 Timothy 2? Importantly, the immediate context of Paul’s instruction here is a discussion of the way followers of Christ should conduct themselves in corporate worship, and the following chapter is a discussion of the qualifications of ordained and elected officeholders in the church. In this context, “teaching” and “exercising authority” are most likely equivalent to exerting authoritative rule over God’s people through preaching and interpreting his word in corporate worship and in other official governing capacities that are the domain of ordained officeholders. Paul isn’t contrasting the inherent dignity and capacities of male and female Christians, since in this respect “all are one in Christ Jesus,” as he says elsewhere (Galatians 3:28). All are called to exercise the gifts freely given by God in ways fitting to each.

Paul’s point, then, is that the way Christians worship God in public assembly before a watching world, and the way that we structure the official institutional and communal life of our communities, should be a fitting witness to the complementary distinctiveness of men and women as created by God in the beginning (and rejected in so many ways in pagan worship practices). That’s why he goes on to speak of Adam being formed first (v. 13). Paul may be saying more than that about women teaching— but he’s not saying less.

The CCB Session resolves to:

• Seek to faithfully uphold both the Bible’s affirmation of teaching gifts and skills given to Christian women for the good of the church, as well as the explicit prohibition regarding women teaching or exercising authority over men in 1 Timothy 2. The Session feels the most consistent way to uphold both these strands of the biblical witness is not to pit them against one another, or ignore one at the expense of the other, but to recognize that Paul’s restriction in 1 Timothy seems to apply specifically to women preaching or teaching in an official capacity within corporate worship services and to serving as ordained officeholders in the church.

• Explore additional discipling opportunities for women in our church who are well-equipped to teach. In particular, we want to explore opportunities for women to teach in non-worship settings beyond women’s and children’s ministry (such as adult workshops).

• Exhort the men of CCB, whether or not they are or will be called to an ordained office, to aspire to grow into the qualities listed for elders and deacons, since “if anyone aspires to the office of overseer, he desires a noble task” (1 Timothy 3: 1). We do this noting the propensity of men to remain silent as Adam did, being tempted to abdicate their callings in the church and in the home.

• Pray for and encourage both the men and women of CCB to embrace their callings as they follow Christ and lead a godly life, putting their shoulder to the plow in the ministry of his gospel and the mission of his kingdom.